“How’s everyone holding up?” This is the occasional check-in I see from my artist friends who are still active on Facebook, a platform many are increasingly abandoning. In groups dedicated to discussing the shift to online and hybrid teaching during the pandemic, the tone of these check-ins is far more serious. Many artists are on edge, feeling frustrated, and in some cases, genuinely fearful about returning to physical classrooms. Meanwhile, the Black Lives Matter movement continues to lead peaceful protests against racial violence, while our government seems intent on stifling alternative spaces for artists in cities once seen as havens, outside of major hubs like New York or Los Angeles.

As we adapt to what feels increasingly like a broken system, the question arises: what’s next? In cities where galleries are closing and essential services are drying up, what drives artists to continue living and creating in this new reality?

As someone who has lived in cities, suburbs, and now rural areas, I’m still grappling with these questions. A decade ago, I left Los Angeles and returned to my hometown of Nashville for a variety of reasons. My move was meant to be temporary, but as I settled in, I entertained the possibility of making it permanent. I had the luxury of space and a slower pace of life, but I wasn’t prepared for the impact of conservative politics on my day-to-day existence. I had spent 25 years in a progressive bubble, believing that the South had largely moved past its old racial divisions. But after Tennessee’s overwhelming support for Trump in 2016, I felt a stark realization: the political polarization of the country had reached a boiling point. Despite my efforts to have conversations and educate those around me, I was deeply disappointed and angered by the lack of action or awareness among some people in the South.

At that point, I started to make plans to leave. I vividly remember hearing Jerry Brown, then governor of California, deliver his state of the state address, declaring his commitment to defending everyone who had come to California for a better life. His words resonated deeply with me. I wanted to live and work in a place where I was proud of my leaders and felt supported by my community. Soon after, I packed up and moved back to California, settling in the unincorporated town of Joshua Tree, with a population of around 8,000. It’s a place with only one highway and limited exits, giving it a unique, small-town charm. As more people from Los Angeles relocated here, we began jokingly referring to the area as “East LA.”

I’m fortunate to have a part-time teaching job, given that jobs in this area are scarce. With five acres of land, I’m able to make art while documenting my new life in the desert. But I wasn’t expecting to find the same political divisions here as I did back in Nashville. When I first moved, I was told the community was a mix of artists, military personnel, veterans, and right-wing Christians, all coexisting peacefully. However, after the tragic death of George Floyd, the atmosphere in the community shifted. Local businesses and galleries put up Black Lives Matter signs in solidarity, only to be met with white supremacist pamphlets, graffiti, and reports of hate crimes in the area.

Now, I find myself questioning how to navigate life in a place where people hold vastly different political and social views. Can we shop, eat, and support local businesses while avoiding contentious issues? Is it possible to engage in meaningful conversations about art without sparking public conflict? These are the kinds of challenges that shape our efforts to expand the reach of art and make it more inclusive.

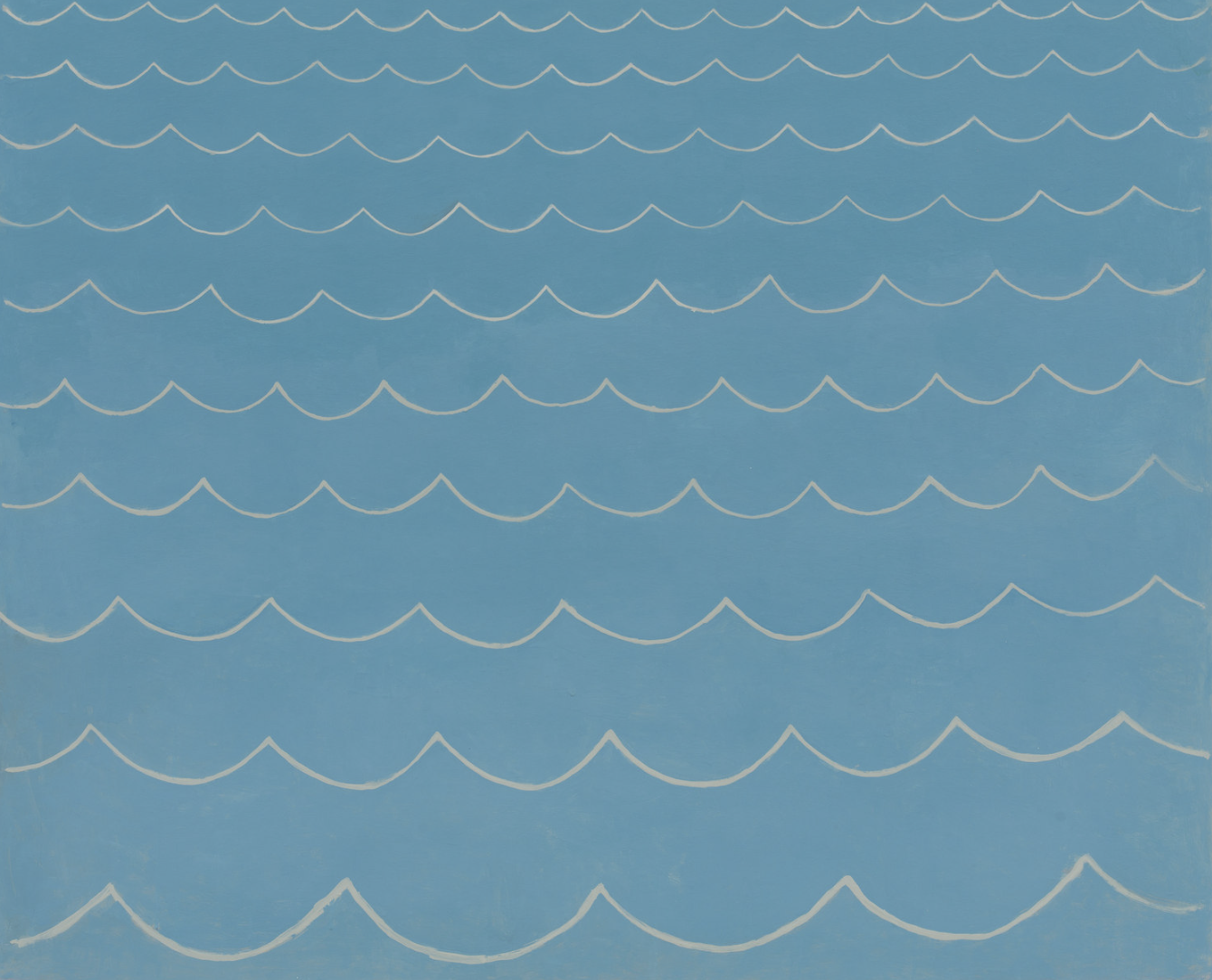

Despite the tensions in the community, there are those who continue to try to make a positive impact. Emily Silver, an artist and curator who relocated from Los Angeles, has worked to create spaces that encourage dialogue and reflection. She co-founded Unpaved Gallery in Yucca Valley, an artist-run project space housed in a shipping container. Though the gallery is temporarily closed due to the pandemic, Silver has found other ways to contribute to the community. Drawing on her background as a yoga practitioner, she started Untamed, a virtual yoga studio with an activist focus. The studio donates a portion of each membership fee to organizations supporting Black Lives Matter, equity in education, and women’s rights, among others.

Silver’s work as both an artist and a curator reflects her commitment to addressing the complex, often painful realities of our time. As she reflects on her creative process, she notes that her current work has become even more deeply connected to the emotions and shifts happening in the world today. For Silver, it’s not just about responding to the moment but also about sustaining the energy for change over the long haul.

Living in Joshua Tree has certainly offered me a new perspective on rural life and its intersection with politics and art. As I reflect on the contrast between the idealistic image I had of California and the realities of a divided nation, I’m reminded of how crucial it is to continue engaging with one another, despite our differences. It’s not always easy, but it’s necessary if we want to create lasting change and a more inclusive art world.

The pandemic, political unrest, and growing divisions in society have reshaped our lives in unexpected ways. But for artists like myself and others in the community, it’s a call to action—to keep creating, to keep connecting, and to keep pushing for progress, even when it feels uncertain.