The world as we knew it before COVID-19 has vanished, and yet it wasn’t with an explosion or an abrupt shift—just the quiet spread of a virus. Buildings remain standing, the natural world continues its cycles, but our sense of ease and everyday normalcy is gone. The pandemic has introduced a deep, unsettling fear that affects us in both immediate and long-term ways. While we face the immediate threat of illness and loss, there’s also the looming uncertainty about whether life will ever return to what it once was.

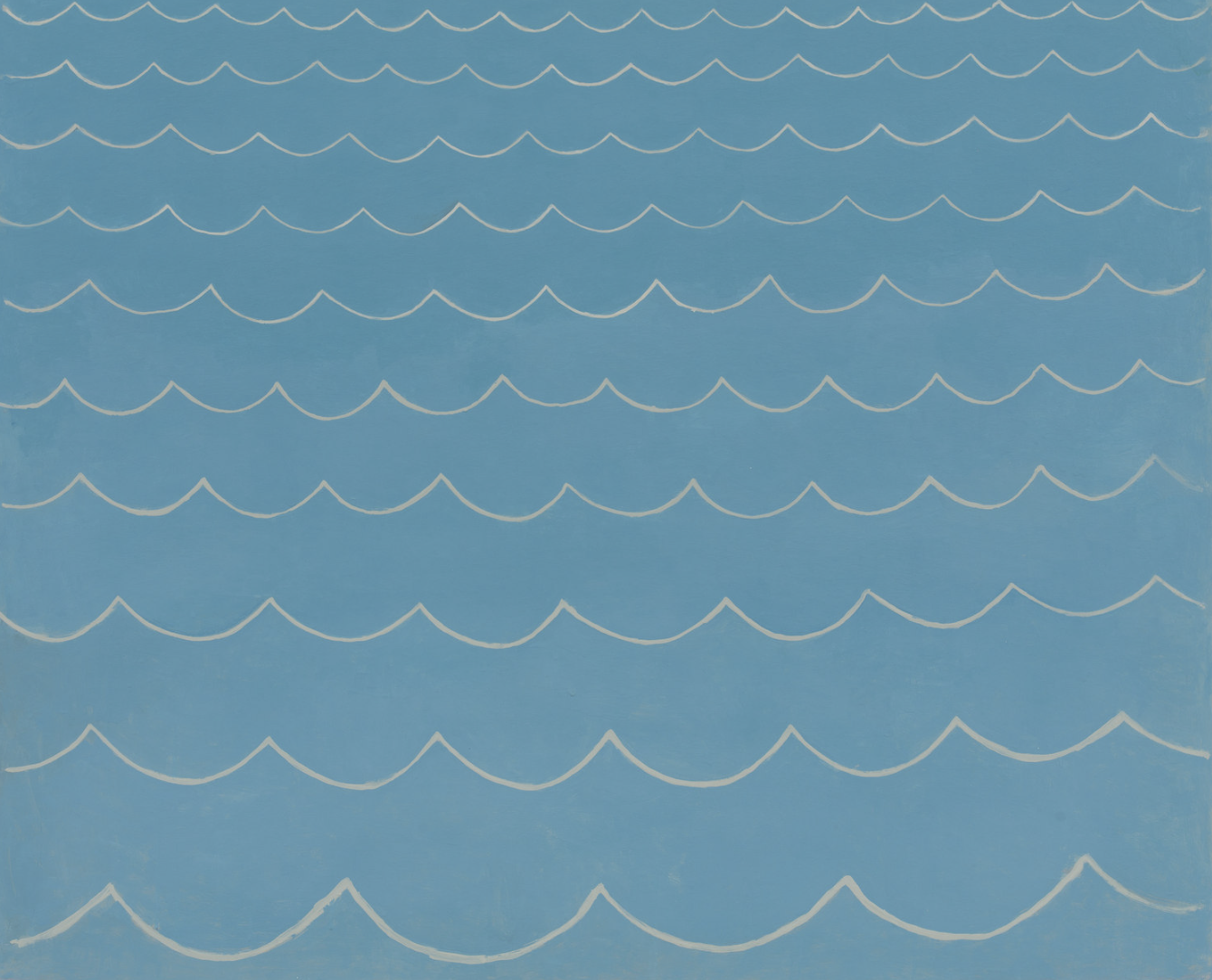

During this time of self-quarantine, I revisited an essay I wrote back in 2002 titled “Confessions of an Abstract Painter.” At the time, I was in my mid-fifties, and I wrote the piece to explain, as clearly as I could, what abstract painting is about, especially for those unfamiliar with the art form. I explained how abstract art isn’t particularly mysterious or elitist—it’s about arranging shapes and colors in a way that resonates with viewers who are open to seeing beyond the figurative. Though I didn’t expect everyone to be drawn to abstract art, the satisfaction that I found in it was enough.

Reading that essay again today, I find myself wondering if I still believe in the same things. As of now, nearly 2 million people in the U.S. have contracted the virus, with over 132,000 deaths. Worldwide, the numbers are staggering, and yet, the true trajectory of the pandemic remains unclear. Some experts suggest that we may need to learn to live with COVID indefinitely. Meanwhile, economies are in turmoil, and children, isolated from their peers, struggle to understand their place in the world. Humans aren’t meant to live in isolation, and yet that’s what many of us are facing right now.

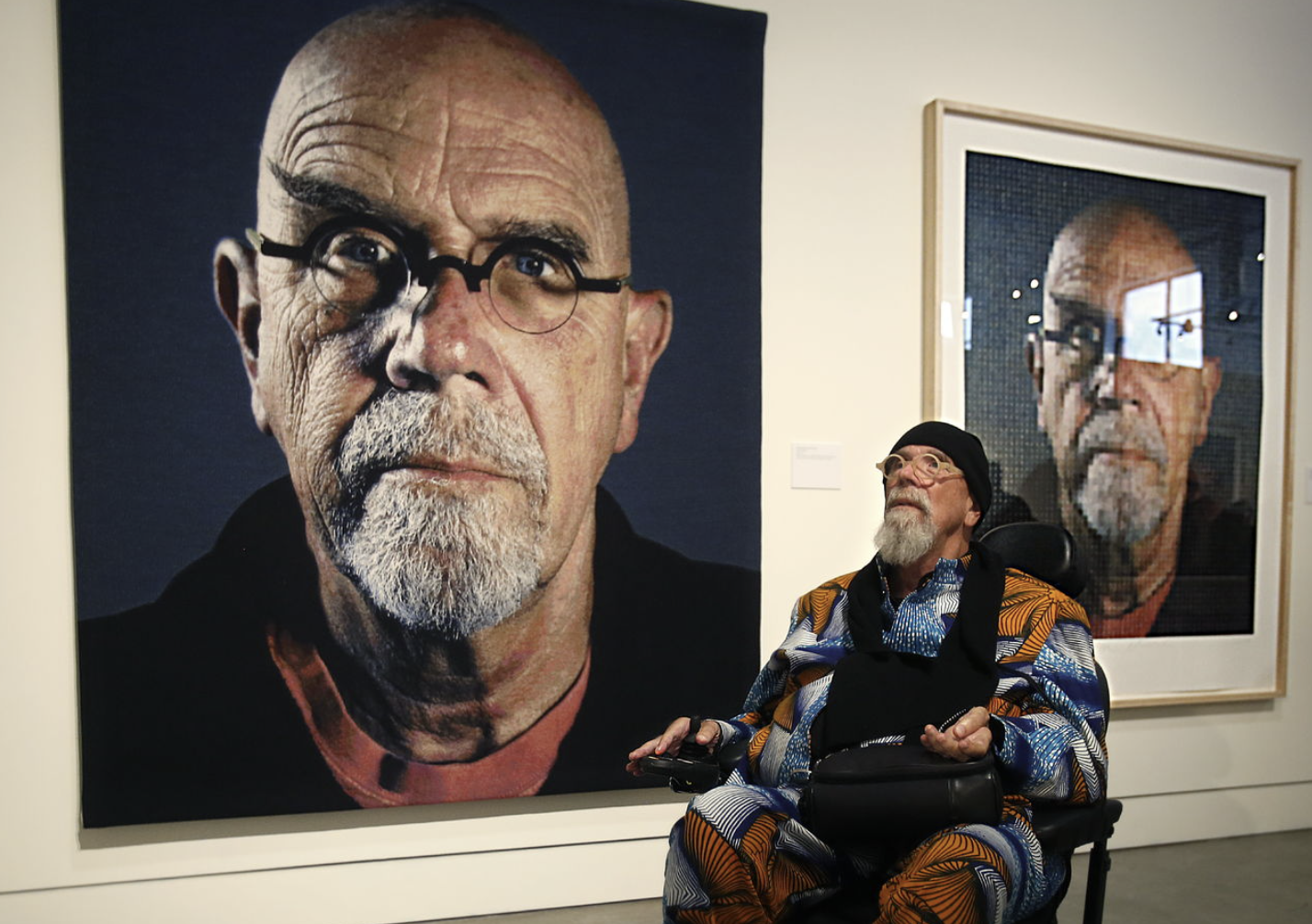

What does all of this mean for abstract painters, like myself, who have always found their space in the art world in very specific ways? The traditional world of galleries and exhibitions, the physical community of artists engaging with one another—this has been severely disrupted. While some embrace virtual spaces to view art online, the experience is hardly the same as standing before a unique, physical painting. For abstract artists, who have always had a small, niche audience, the pandemic has effectively erased that audience. With no figurative narratives to tell or high-tech innovations to flaunt, abstract artists often find themselves in a lonely middle ground.

COVID-19 has made the isolation we already felt as abstract artists more pronounced. The early Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s and 50s often felt a sense of loneliness and existential anxiety, but they were able to find solace in their physical gatherings—debates, discussions, and social interactions. Today, even these small comforts are missing, and the community we once had is increasingly fractured.

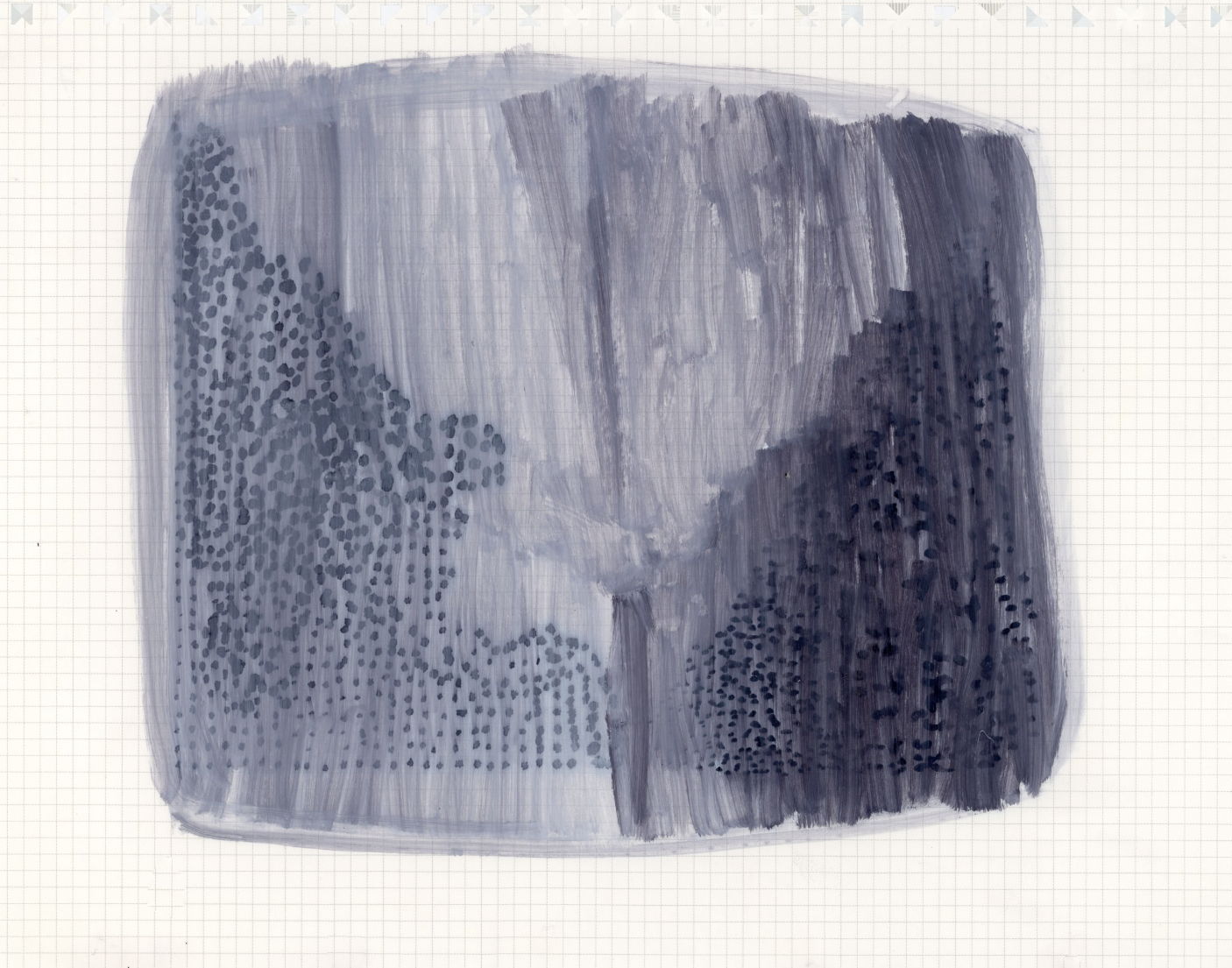

As I reflect on my own art practice, I realize that nothing in my studio has changed because of the pandemic. I still paint the same way I always have—arranging colored shapes on a canvas. The daily routine remains unchanged, though external circumstances have become more strained. But lately, with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, I’ve started to question whether abstract painters like myself are doing enough. Is it enough to keep creating art that has no political or social impact when the world outside is demanding change?

The murder of George Floyd has sparked protests and a reckoning with systemic racism, and yet, abstract painters continue to create their works in isolation, without addressing the issues at the heart of these movements. It’s a discomforting thought: are we, by focusing solely on our craft, complicit in maintaining the status quo? Are we too focused on preserving an old, European-centric legacy of abstraction to address the pressing issues of our time?

The truth is that contemporary abstract painters are heirs to a long line of artists, but our work often feels like a mere echo of the past. The early modernists paved the way for abstraction, and now, we’re left trying to find our own path in an increasingly skeptical and socially aware world. Abstract art, once seen as groundbreaking, now faces questions about its relevance in a time when society demands more than aesthetic beauty.

In my 2002 essay, I referenced Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein, where the character advises against being completely absorbed by the era you live in, suggesting that one must engage with the present without being entirely consumed by it. This has always been a challenge for me—how can I participate in the world of today while maintaining some detachment from it, especially when my work is so deeply tied to my emotional and intellectual responses to the world?

The unsettling part of the pandemic for abstract artists is not the absence of a physical audience—it’s the ongoing struggle to make meaningful work in a time when our audience is either inaccessible or disinterested. For many years, abstract painters have created work without fully knowing who exactly is engaging with it. We paint for ourselves, for our fellow artists, or perhaps for an imagined audience, but we always struggle with this question: who are we painting for?

With the collapse of traditional art world structures, it feels like now is the time to rethink the way we present and share our work. The gallery model, already outdated in many ways, seems even more disconnected in the context of a global pandemic. For abstract artists, the future might involve creating more collective spaces—cooperative galleries where artists can come together and assess one another’s work based on its true quality, not the status of the artist. I hope younger generations of abstract painters will figure out how to push the boundaries of how and where we display our art.

In the end, abstract painters are left to navigate these uncertain times in the same way we always have—creating work, trying to find purpose, and hoping that somehow, amidst all the chaos, we can find a way to reach an audience that still values what we do. The need for validation—whether it’s through social media “likes” or gallery exhibitions—remains, but it’s a more fragile hope than it’s ever been.