In October, I had the opportunity to participate in the residency program at the Burren College of Art, where I spent my time exploring the region through photography and painting. The Burren, located in County Clare in western Ireland, is a UNESCO Global Geopark, renowned for its distinctive geological, archaeological, and cultural significance. Below are excerpts from my journal, accompanied by images capturing the essence of my journey.

My arrival in Ireland was early in the morning. After a taxi ride from Shannon Airport, I found myself heading to the Burren College of Art, passing through a dark, gloomy landscape. The early light from the rising sun mingled with car headlights, casting an eerie glow on the lunar-like terrain. As I arrived at Newton Castle, I was exhausted and went straight to my room to sleep until midday. When I finally woke up, I ventured out to explore the campus and climbed the tower of the Newtown Castle. From there, I gazed out over the karst landscape, which had been shaped over millennia by the dissolution of limestone. The view was captivating, offering a glimpse into one of Europe’s most extensive karst landscapes. I then explored the studio and met the dean briefly, before heading out again to experience more of the surrounding area. The weather was unpredictable, shifting between clouds and sunshine, and the rocky terrain was marked with hues of purple and gold.

At the dean’s recommendation, I hiked up Newtown Trail, which led me beyond the sparse “tree line” of thorny hedges and blackberry bushes. From here, I took in the stunning landscape, with its perfect green fields giving way to the barren, jagged limestone mountains. I took frequent breaks, sampling the ripe blackberries along the way. As I climbed higher, the terrain became steeper, and I encountered ancient stone fences, tawny cows, and lively seabirds. While examining a piece of limestone shaped like an hourglass arrowhead, I accidentally shattered it in my hands.

On my first full day, I walked the Wood Loop Trail from Ballyvaughan back to the castle. The day began overcast, with drizzle turning into light rain. The lush greenery along the trail was striking, with vibrant blackberries covering stone walls and abandoned homes. As I walked, I noticed cattle grazing nearby, and birds of prey soaring overhead. I paused at a scenic spot to paint a small watercolor of Aillwee Mountain, though the rain eventually made it difficult to continue, forcing me to pack up and head north to Ballyvaughan.

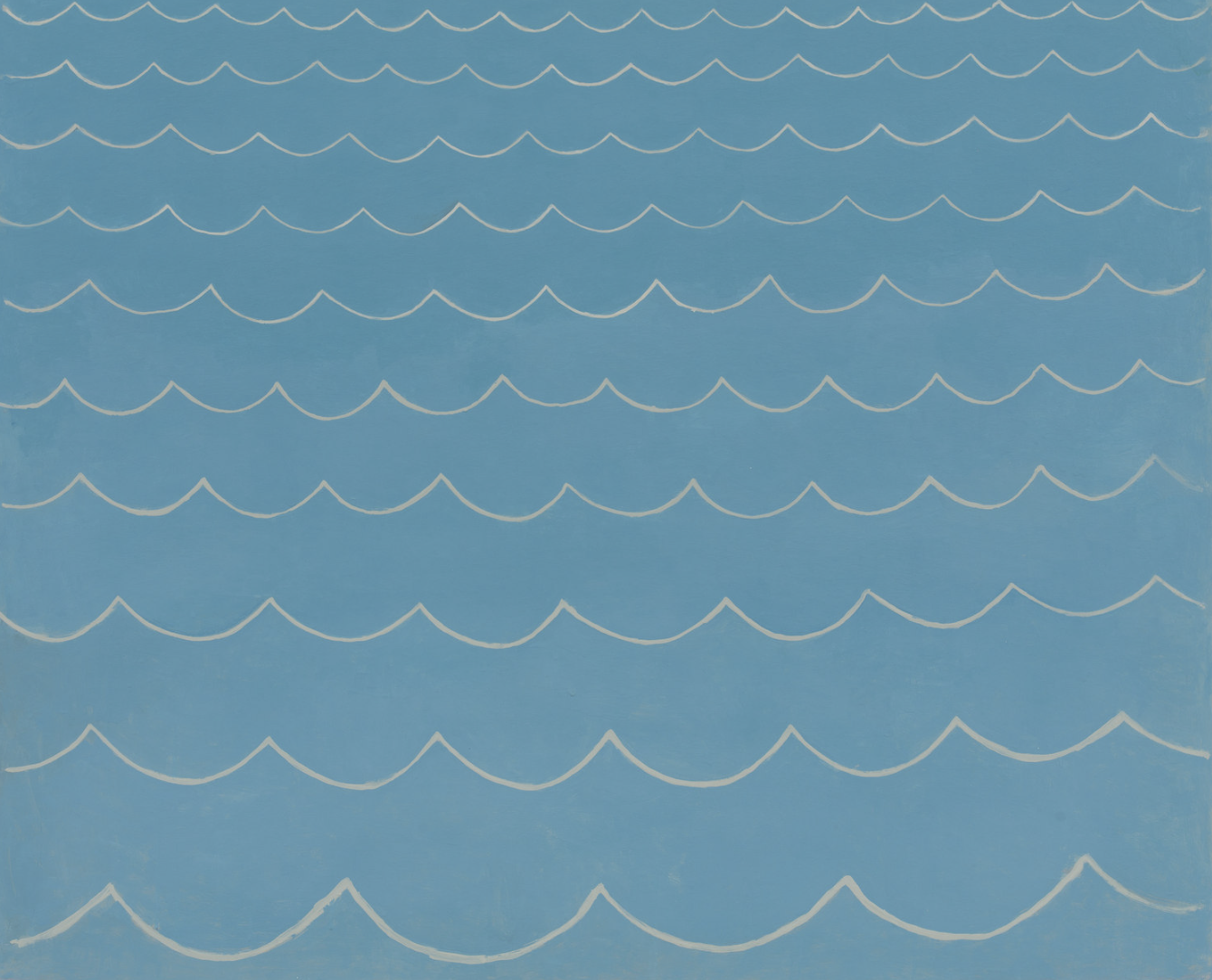

The weather in Ireland proved to be a constant influence on my work. The next day, I decided to paint the cliffs near the castle. The weather fluctuated wildly, with rain and hail mixing with bursts of sunshine. Despite the unpredictable conditions, I managed to complete two small paintings: one of the cliffs and another of the valley. The hill behind the castle, known as Cappanawalla, turned out to be much larger than I anticipated, stretching all the way to Black Head Point by Galway Bay.

The following day, I embarked on a more ambitious walk around Cappanawalla. The sky was clear, and I hoped to reach the bay or perhaps circumnavigate the mountain. As I climbed the valley past Cahereen, the weather became more unpredictable. By the time I reached the trail intersection near Black Head Loop, the wind had picked up to gale force, and sheets of rain made progress impossible. I decided to head toward the sea, but the terrain soon became too treacherous to navigate safely. Reluctantly, I turned back, though I couldn’t help but feel exhilarated by nature’s raw power. It was a humbling reminder of the uncontrollable forces of the wild Atlantic.

Back in the studio by sunset, I couldn’t stay indoors for long. The following day, I worked in the digital lab before heading back out to paint. I captured the beauty of the landscape, from the sheep dotting the hills to the breathtaking views of the surrounding mountains. Later, I walked down the lane to a famine village ruin, where I painted the distant peaks, their outlines framed by the shifting light.

In the days that followed, I continued to explore the Burren, hiking through diverse terrain, visiting ancient ruins, and painting the ever-changing landscape. I trekked to the wedge tomb of Gleninsheen, a Neolithic structure nestled in a pasture, and then on to Poulnabrone, another well-preserved wedge tomb. The weather had been unpredictable, but I was fortunate to have clear skies during my visits to these historical sites, which felt both timeless and serene.

One of my goals during this trip was to visit Richard Long’s stone circle near Doolin Point. After a bit of wandering over the lunar-like surface of the Burren, I finally found the sculpture, A Circle in Ireland, a work from 1975. Set against the dramatic backdrop of the Cliffs of Moher, Long’s piece is minimalist but perfectly complements the surrounding natural landscape. The circle, surrounded by ancient stone walls and cairns, blends harmoniously with the Burren’s rugged beauty.

As I wrapped up my journey, I reflected on the beauty of the Burren and its intricate interplay of nature and history. The landscape itself felt like a work of art—sculpted by time, wind, and water—and my time spent there underscored the importance of preservation. Just as Long’s ephemeral art remains in dialogue with the landscape, the Burren’s natural and archaeological wonders continue to inspire those who visit.